媒体评论 13.04.22

Zolima City Mag, « The Space Between: Zao Wou-Ki’s Life and Work » by Ilaria Maria Sala

“Everyone is bound by a tradition. I am bound by two.” With this deceptively simple statement, Zao Wou-Ki, born in Beijing in 1920, explained his hyphenated identity as a French-Chinese painter. His early artistic education took place in China, at a time when everything in Chinese society was in huge ferment. Republican China (1912–1949) was still establishing itself, as domestic instability and the beginnings of the Japanese invasion made everything feel precarious, but also energetic and full of possibilities – in art, as in every other aspect of life.

Zao had moved to Shanghai with his family when he was just a few months old. At the age of 15, he passed the entrance exam for the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts (today, the China National Academy of Fine Arts), the most prestigious art school in the country. There, he chose to study with Lin Fengmian (born Lin Fengming), and to learn from him how to paint in the Western tradition instead of undergoing a training as a classical Chinese painter, which involved long sessions of copying the work of the ancient masters, a prospect that did not at all appeal to him.

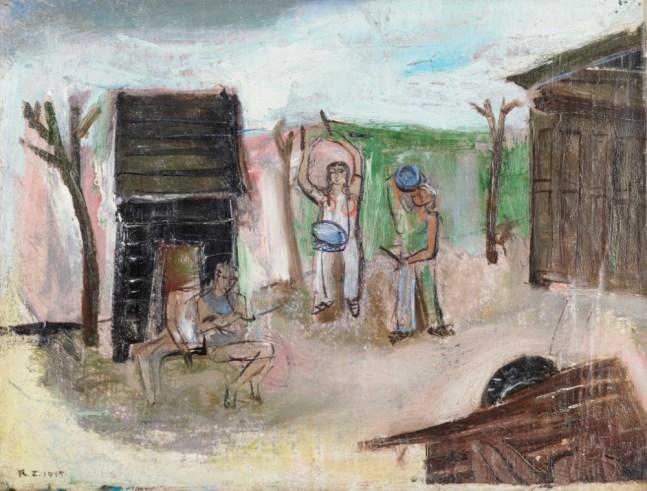

Open air theatre, 1945, oil on canvas, M+ Hong Kong

No title, 1949, aqua paint, private collection, courtesy Gallery Villepin, photo by A. Mercier

Lin was probably the most innovative Chinese painter of the time, one who theorised a synthesis of Chinese and Western art. Born in Guangdong in 1900 to a classical Chinese artist, he trained in Paris and had a somewhat iconoclastic view towards the constraints of the Chinese tradition, which he wanted to modernise. He managed to shock his conservative audience by painting square canvases, instead of the long scrolls on silk favoured by more traditional painters, as was expected of him. His teaching was revolutionary: three of his students would become some of the greatest names in contemporary Chinese art. They were Wu Guangzhong, Chu The-chun and Zao Wou-ki – a trio sometimes referred to as the “Three Musketeers” of Chinese art. They were accomplished artists capable of fusing Chinese pictorial tradition and techniques with Western ones, producing impactful works of high beauty and modernity that continue to be widely admired and coveted by galleries, museums and collectors.

In 1948, influenced by Lin, Zao too decided to go to France with his first wife, Xie Jinlan, who later became a painter as well. He didn’t yet speak a word of French, but he was determined to learn about Western art directly in a place that was a magnet for the artists he had studied under Lin: Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti. He wanted to express himself in a wider artistic register without being confined to Chinese tradition, as vast as it may have been. He and Xie sailed off to France by boat and reached Marseille before moving on to Paris. Zao’s first stop in the capital was the Louvre, which he described as “an extraordinary shock.”

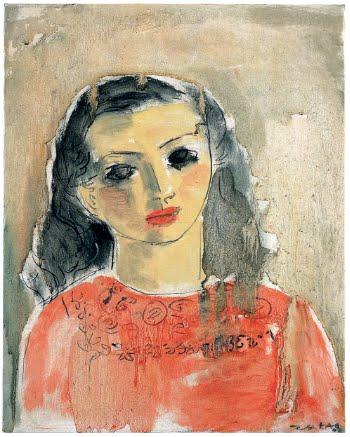

From this time onward, Zao starts forging his own path, developing a unique style which he will adapt to his paintings, no matter what media he will be working in. In a 1986 interview with the French radio station France Culture, Zao said, “I do not think we can still talk about Chinese and Western art: this frontier has been totally broken.” And he is undoubtedly one of those who broke it down. Once in France, he did not want to be labelled as a Chinese painter, which he felt would pigeonhole him and limit his scope, and for this he refused to work with ink for a full 24 years of his career, to avoid being stereotyped. He worked in oil, charcoal, sanguine and watercolour, with prints and gouache, allowing his style to fluctuate along the different inspirations he was receiving from the artists he was getting to know: some of his oil paintings show his lifelong devotion to the art of Cezanne and Matisse, evident in his early portraits (like his oil “Portrait of My Wife,” 1949), while his recent discovery of Paul Klee’s work full of symbolism inspired him to move towards abstraction.

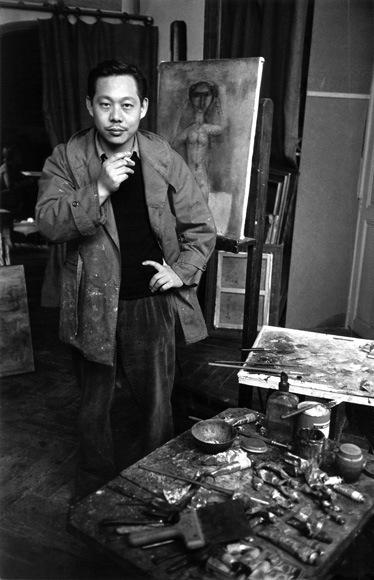

Zao Wou-ki, 1950s – Photo by Mark Shaw, courtesy Villepin

Portrait, 1947, private collection, courtesy Gallery Villepin, Photo by D. Bouchard

Zao’s life seems to have been particularly shaped by a series of lucky encounters, and lifelong friendships. In 1949, as he was still finding his footing in Paris and taking classes at the Académie de la Grande-Chaumière, he met abstract artists Jean-Paul Riopelle, Joan Mitchell, Maria Helena Vieira de Silva. He made lifelong friendships, such as with Pierre Soulages—who would become a “brother” to Zao—and the architect I.M. Pei, with whom Zao would travel back to China in the early 1980s to work on the Fragrant Hill hotel in Beijing. Joan Mirò and Alberto Giacometti were also among Zao’s close associates. Henri Michaux was particularly influential—“Michaux made me,” Zao once said—as he brought Zao’s work to the attention of important art critics and collectors, especially Pierre Loeb, who ran Galerie Pierre, which helped launch the careers of many prominent mid-century artists. It’s where Zao met Riopelle and Vieira de Silva and was introduced to Pei.

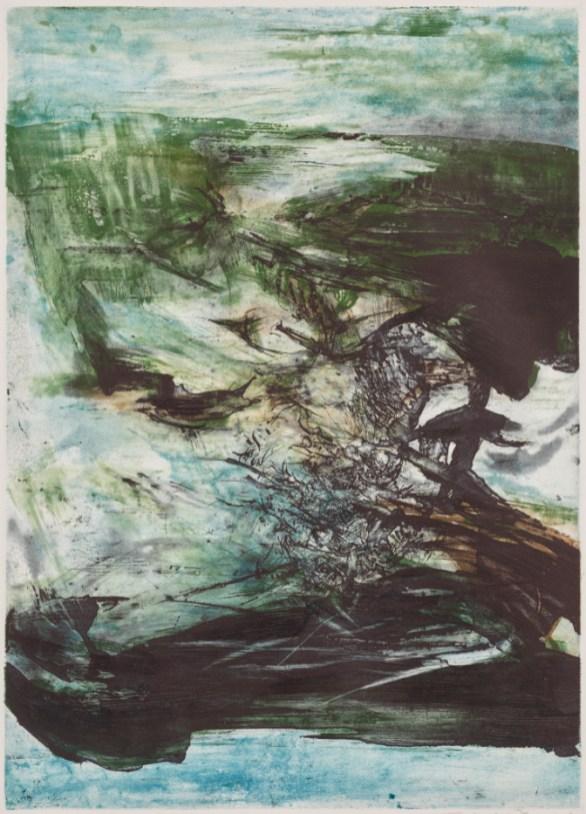

Michaux and Zao both worked at the same lithographic studio run by Edmond Desjobert. It’s an important detail in Zao’s story, given that his prints, while still overshadowed by his majestic paintings, are now becoming more popular. Hong Kong’s own M+ museum has just received a donation from Zao’s daughter, Sin-May Roy Zao, of 12 works by Zao, of which nine are prints, along with two oils and one watercolour, spanning his entire career.

Ville Engloutie, 1955, oil on canvas, private collection courtesy gallery Villepin, photo by A. Mercier

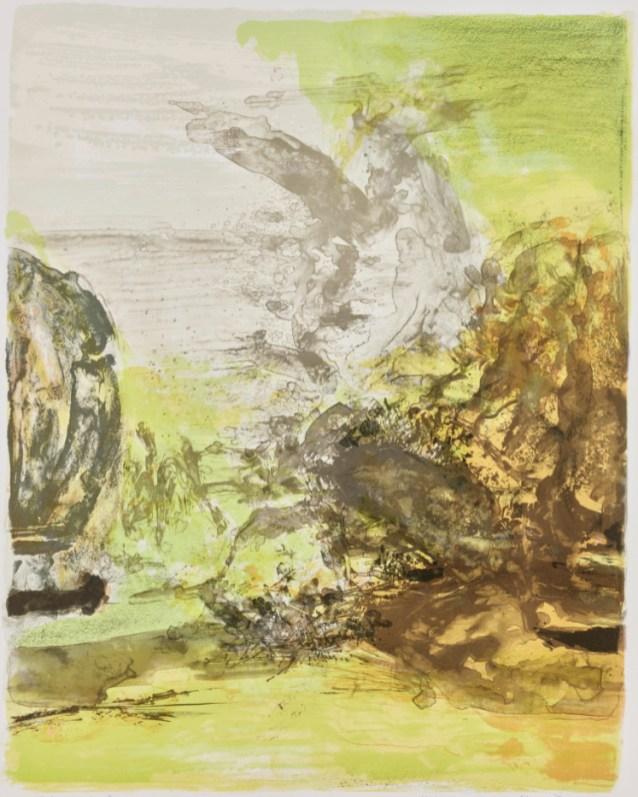

Lesley Ma, former ink art curator at M+ and current associate curator of Asian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, says that Zao returned to prints throughout his career. “Every few years he would concentrate on prints for a few months, to really explore the medium,” she says. “The print studios in Paris were already world famous, for their specialised ways, or for their ability they had to create unique relationships with the artists. So the prints allow us to see another side of Zao, more subtle, lyrical, but still very bold and majestic in its own way. In the print works, you really see his usage and his integration of Chinese ink painting and calligraphy aesthetics into this kind of medium that is really process-oriented.”

In a sense, it is as if print allowed Zao to experiment more boldly, without feeling the constraint of his self-imposed abstinence from ink. “Within the print medium he was testing how to incorporate that kind of calligraphic understanding, the interest in different aspects of binds and of marks, and the saturation of ink and materials in his work,” says Ma. “It was really an interesting playground for him.”

But while not wanting to be pigeonholed simply through his geographic provenance, Chinese culture and tradition was still a decisive part of his art. In the 1950s, inspired by Paul Klee’s abstract symbolism, Zao incorporated signs in his own paintings and started the Oracle Bone series, which marked a reconnection with his Chinese heritage. Inspired by the scapular bones and turtle plastrons used in rituals during the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BC), Zao used the vastness of the canvas to pour a cascade of ancient oracle bones characters in the midst of imaginary landscapes and dazzling colours.

In 1957, Zao travelled to the United States for the first time, along with his friends Pierre and Colette Soulages, who eventually introduced him to gallerist Samuel Kootz, who ended up representing the artist in the US. Although Zao had already begun to work with abstract painting, he was so enthused by Abstract Expressionism, which was one of the dominant forces in the American art scene, that he fully embraced abstraction and left any symbolism.

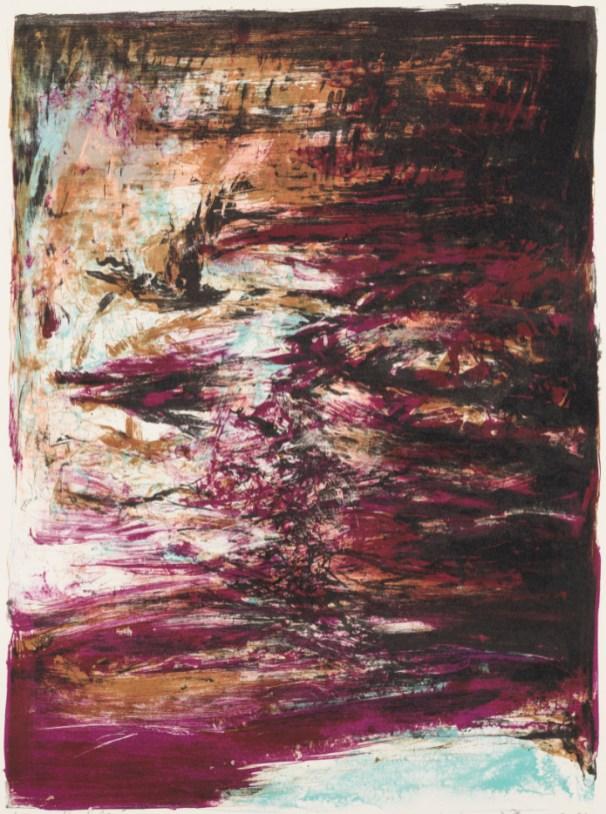

Untitled, 1969, etching with aquatint and Untitled, 1968, lithograph

M+ Hong Kong, photo, photo by Lok Cheng & Dan Leung

Untitled, 1969, lithograph, M+ Hong Kong, photo by Lok Cheng & Dan Leung

Very soon, Zao’s work started to be appreciated by a growing number of well-connected people, like the writer and minister of culture André Malraux, who eventually helped Zao secure French citizenship. By 1958, when he was already represented in France by the influential Galerie de France, Zao went back to Asia for the first time, spending six months in Hong Kong after a visit to Japan. He was treated like a star and followed everywhere by the local press, who were fascinated by a Chinese painter who had managed to become famous abroad.

Although he did not spend much time in Hong Kong, his visit changed his life: it was here that he met and married the actress Chan May-kan, who returned with Zao to Paris and took the name May Zao. She abandoned acting and began pursuing abstract sculpture. But after just ten years, she began to suffer from dementia. Zao was too distraught by her decline to concentrate on his big oil paintings. This is when he reconnected with ink. He began making small Chinese ink drawings to keep himself busy and to stay in practice. When May committed suicide in 1972, Zao was devastated by this loss, and when he finally returned to oil, he transposed his pain onto the canvas.

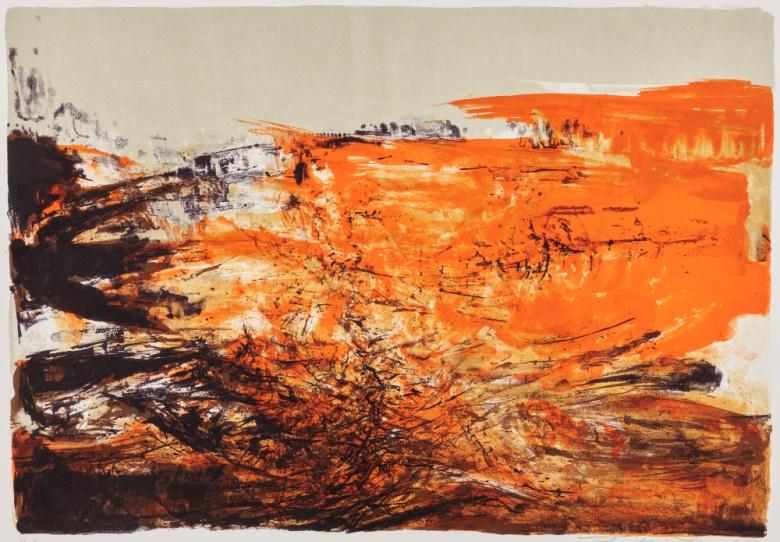

Guiding visitors through a recent exhibition of Zao Wou-Ki works at the Villepin gallery on Hollywood Road, curator Cyrus Lamprecht notes the change in Zao’s work. “You can see the anger in his brushstrokes and choice of colours,” he says. The years following May’s suicide are characterized by large oil paintings in dark browns and black; they hint at cosmic landscapes in which something ineffable and tumultuous is taking place. Through his powerful use of light, it is as if Zao was questioning the very nature of life, of its end, and of its incomprehensible rhythms.

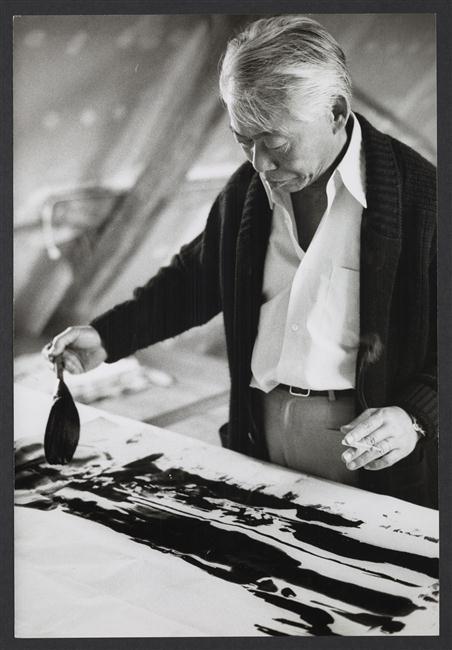

Zao Wou-ki, 1980, photo by Michel Delaborde

via RMN-Grand Palais, Courtesy Villepin Gallery

Untitled, 1989, lithography, M+ Hong Kong,

photo by Lok Cheng & Dan Leung

Light is one of the main forces that Zao employs on his huge canvases, and the larger the work, the more light plays a crucial role. This was in part due to the way in which he would only trust natural light for his work. Yann Hendgen, art director of the Zao Wou-Ki Foundation in Geneva, recalls that Zao used to spend all his days in his studio, working. “‘Work, work, always work,’ he often said. Painting was a real obsession for him and there never was a day without him painting.”

That made travelling quite difficult for Zao; he didn’t want to spend time away from his studio. “It was a closed space with few openings, because he didn’t want interference from the outside world,” says Hendgen. Zao painted by natural light, which came into the studio through a large north-facing zenithal glass panel. This allowed him to see colours as they are, with all their nuances, without being distorted by the light of the sun. He did not paint at night for the same reason; artificial light altered “the truth of colours,” as Hendgen puts it. He also notes that “music was always present in his studio.” Zao was a gifted opera singer, and his studio echoed with the sound of Mozart and Bach, “but also of free jazz, and Edgar Varèse, Heinrich Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez.”

Untitled, 2006, triptyque, 195 x 291 cm, photo courtesy gallery Villepin

From the 1970s onward, Zao fully embraced his cosmopolitanism, which is present in the very way in which he wrote his name. Lamprecht draws attention to the artist’s peculiar signature: Zao written in Roman letters, Wou in simplified Chinese and Ki in traditional Chinese. It is perhaps worth noting that Zao’s given name (mou4 gik6 無極) translates as “no boundary.”

The last boundary in Zao’s life was removed in 1983 when he was officially invited to return to his homeland for his first major exhibition in China. (He had managed to go back to China in the early 1970s in order to visit his family and to work later on I.M. Pei’s Fragrant Hills project, although his renown had not yet reached China; at that point, the country was still in the midst of the Cultural Revolution and closed off to the world.) He took his role as a bridge between the two geographical poles of his life seriously: in 1997 and again in 2000, he accompanied French president Jacques Chirac on his state visit to China. In 2006, Chirac awarded him with the Légion d’Honneur, one of many official accolades he received in France.

By then, Zao’s large works were already being collected by museums and foundations, and even some Chinese institutions started to commission large-scale pieces for public display – closing a loop that had started in the 1930s in Hangzhou. Zao died in 2013 at his home in Switzerland, but his legacy lives on. With the recent donation to M+, Hong Kong too is now even more strongly part of this incessant weaving of connections and exchanges, which has contributed to the creation of Zao Wou-Ki’s genius.

Zao Wou-ki, the Eternal Return to China runs until May 22, 2022 at Gallerie Villepin. For more information please click here.