Portrait de ma femme

1949, Oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm

Photo Dennis Bouchard

For Zao Wou-Ki, Paris was a place of new connections and pictorial discovery. His early Paris paintings were full of numerous influences and at times, his portraiture is close to that of Jules Pascin, with a focus on the line and drawing. At others, his blocks of color echo those of Henri Matisse, as in Portrait de ma femme. His female nudes in charcoal, sanguine and pencil also contain influences of Aristide Maillol.

Oil on canvas, 81 × 100 cm.

Rights reserved

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Rights reserved

Zao Wou-Ki made still lifes using all mediums. Between 1948 and 1954, he painted more than 30. His use of the single graphic line –the floor line or the edge of a piece of furniture – as an indication of depth, is another influence of the work of Paul Cézanne.

His themes of inspiration during this period included fruits (lemons, grapes, figs), flowers (lotus, hydrangea) and animals (fish). He also represented familiar objects (teapots, glasses, bowls, vases and tea cups). Nature morte au Biba, 1952, represents a stringed instrument typical of Chinese music that he kept in his studio at this time.

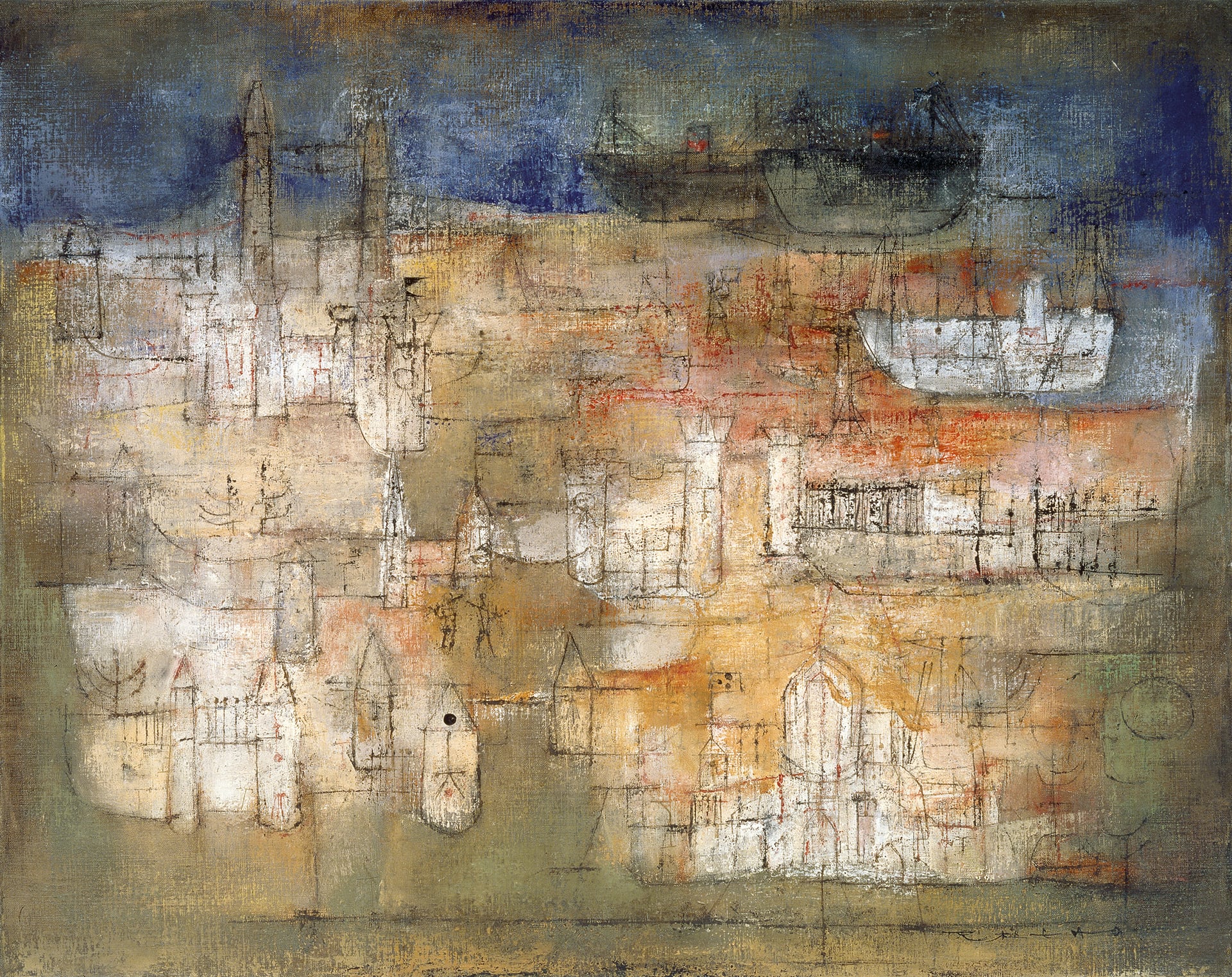

Paysage boréal, 1953

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Rights reserved

He went to the UK in 1952, but did not paint in his sketchbook. Instead, he transposed his memories the following year, producing a poetic vision of London’s topography, juxtaposing the Tower of London, Tower Bridge, Westminster Abbey and boats on the Thames.

Centre Pompidou, musée national d’Art moderne / CCI, Paris, France.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

By the early 1950s, Zao Wou-Ki felt trapped in figuration. The work of Paul Klee would take him in a new direction. Like Klee, he decided to use signs and symbols as he moved further away from strict figurative representation, to invent a language that allowed him to escape the limitations imposed by choice of subject. He re-appropriated ancient Chinese characters for their aesthetic value and invented forms that would take him little by little, ever closer to abstraction. From this point on, he moved into a world without references.

Vent is often considered as his first abstract painting. The figurative element has almost totally disappeared and the long cascade of invented signs has no graphical meaning, evoking instead an impalpable element, the passing wind.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

The figure of Qu Yuan was honored by the Zhao family. On the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, Zao Wou-Ki and his father would throw rice into the water so that the poet would not be eaten by fish. Hommage is a continuation of the family ritual that honors the memory of the great poet: dated May 5, 1955, it evokes watery depths.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Japon.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne / CCI. Held at the Musée d’Art, d’Histoire et d’Archéologie, in Évreux, France

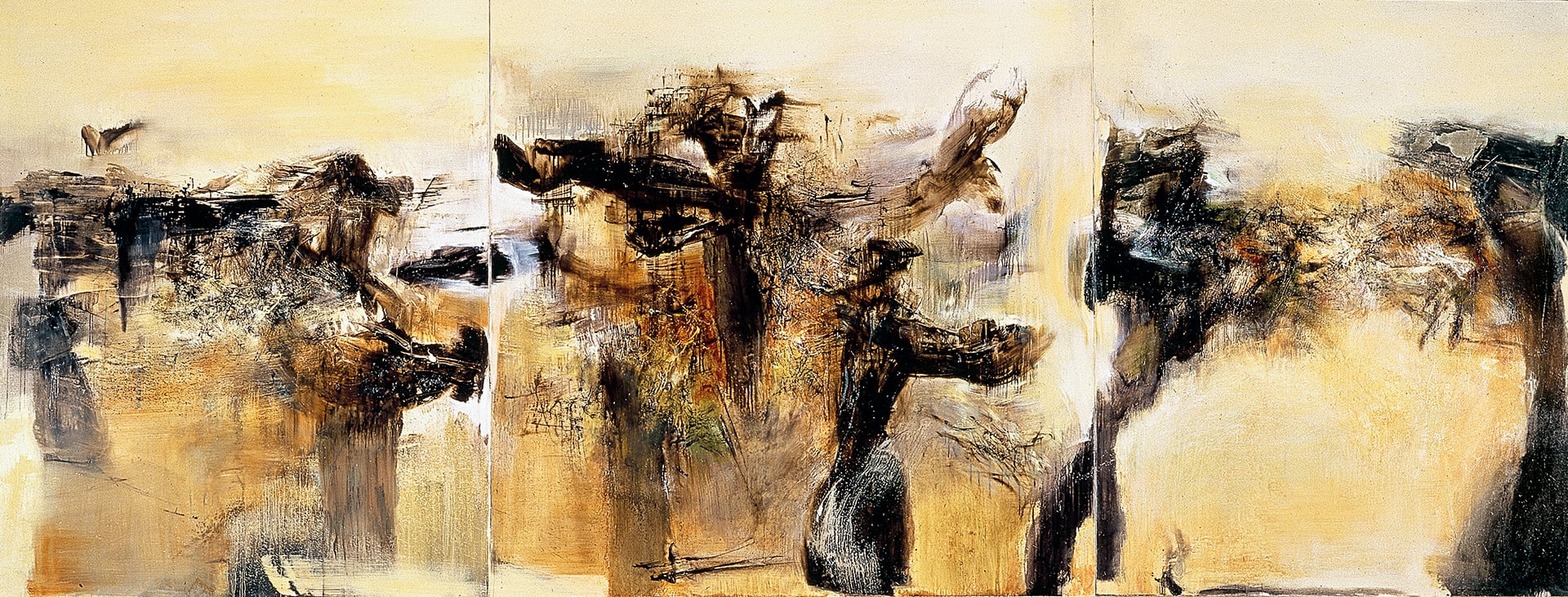

1964, Oil on canvas, 255 × 345 cm.

Musée cantonnal des beaux-arts, Lausanne.

Donation Françoise Marquet-Zao, 2015.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

This very large format work (255 x 345 cm) was painted a year before the death of the composer. It was through Henri Michaux – who also joined Pierre Boulez’ Domaine musical– that Zao Wou-Ki met Edgar Varèse while he was in Paris working on Déserts in 1954. The two men quickly took a liking to one another.

For his tribute, Zao Wou-Ki undoubtedly drew inspiration from Varèse’s music. The dynamic tension and teeming mass movements evoke the sound contrasts and time splits of the composer’s works. Zao Wou-Ki gave the same central importance to emptiness in his paintings, as Varèse gave to silence in his music. They both created a moving space, that dilates and retracts, enveloping the spectator.

National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taichung, Taiwan.

Rights reserved

Ishibashi Foundation, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japon.

Rights reserved

En mémoire de May – 10.03.72

10.09.72 – En mémoire de May (10.03.72), 1972, Oil on canvas, 200 × 526 cm,

Centre Pompidou, musée national d’Art moderne / CCI, Paris, France.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

The work is striking for the strength and violence with which bears witness to his wife’s great suffering. Zao Wou-Ki did not wish to sell it, so he decided to donate it to the French State in 1973, as part of the collections of the National Museum of Modern Art of Paris.

Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japon.

Rights reserved

The Hakone Open-Air Museum, Hakone, Japon.

Rights reserved

Thanks to the Fuji Television Gallery, which exhibited the work in Tokyo in 1977, this important painting has remained in Asia, a continent dear to Malraux. Now owned by Fuji Media Holdings Inc., it is held at the Hakone Open-Air Museum (Japan).

Rights reserved

Rights reserved

Oil on canvas, 200 × 525 cm.

Rights reserved

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Rights reserved

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris, Paris

Donation from Françoise Marquet-Zao, 2019

This painting is inspired by Matisse’s famous work, Porte-fenêtre à Collioure, 1914 (Pompidou Center, National Museum of Modern Art, Paris).

In 1984, he wrote about the work: “ (…) In China they say that Porte-fenêtre is a magical painting, because in front of that door, empty and full at the same time, there is life, dust, the air we breathe. But what happens behind it? It’s a vast, black space. It’s an open door onto real painting for all of us.”

This tribute work in honor of one of Zao Wou-Ki’s favorite artists, remained in his collection until his death. His wife donated it to the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris in 2019, rendering it inalienable and ensuring it could be on permanent public view.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Rights reserved

Rights reserved

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Zao Wou-Ki made this painting in memory of Incendie, an oil on canvas dating back to 1954-1955 (130 x 195 cm). Acquired in 1955 by the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris, the work is unfortunately no longer part of the national collections. Lent out numerous times, the canvas did not return from its last exhibition in Singapore in 1982. Zao Wou-Ki chose to make a fresh reinterpretation of Incendie, more than 40 years after its creation.

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo by Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard

Photo Dennis Bouchard